It's the talk of the town: there's a Black man picketing outside Maude Findlay's house. Maude doesn't know it, though. Not yet. Right now, she's inside babbling green.

“I read all the latest magazines, current books. They all say talk to you, so I’m talking to you! …And you? I said things to you last night I haven’t said to four husbands.”

Peace lily, Dracaena, Monstera, and some kind of ivy stand—rest? grow?—silent in front of Maude. However you're supposed to talk to plants, whatever kind of language you ought to use to get them to grow, Maude ain't got it. She's read all the magazines, she tells the gathered greenery. She's hip to the latest indoor plant advice. Still, no matter how much she talks to the plants in her living room, they won't grow an inch.

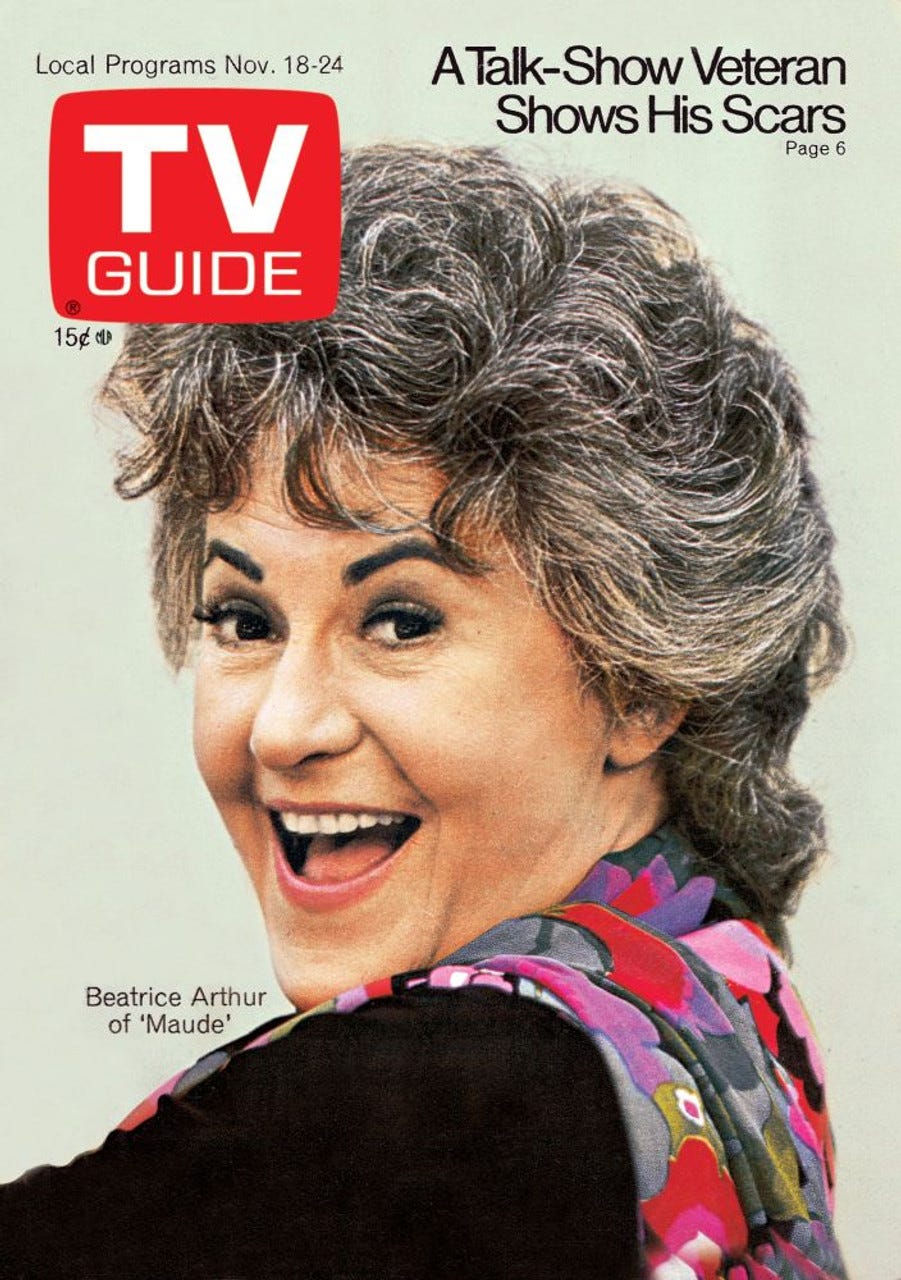

This is the opening of "Slum Lord"—the tenth episode in the first season of Maude. Running from 1972 to 1978, Maude starred Bea Arthur as the titular character more than a decade before she would play Dorothy Zbornak in Golden Girls. They're both tall and deep-voiced, but Maude isn't Dorothy. In fact, she's something like Dorothy's opposite—an outgoing, lively woman with a full social calendar. And unlike Dorothy, Maude talks to her plants. It's part of what makes her so popular, so on-trend.

Just three years before Maude started chatting up her cactus, Cleve Backster, a polygraph expert who had worked for the CIA, published “Evidence of a Primary Perception in Plant Life.” In “Evidence,” Backster argues that plants are able to sense complex human actions in the world and respond in an electronically-measurable way. He came to this conclusion while testing his polygraph machine on the leaf of a Dracaena in February of 1966. Given that a polygraph machine records electrical output, and presuming that plants use some kind of energy to transport water from their roots to their leaves, Backster wondered if the polygraph could detect internal plant activity.1 Backster connected his polygraph leads to a leaf on the Dracaena and watered the plant, expecting to see evidence of water transport in progress. But the polygraph didn't detect any activity. Backster began to wonder how else he might 'excite' the plant in an electrically-measurable way. He started to imagine burning the plant with a match.

According to his own retelling of the incident, the polygraph machine went wild at the instant he imagined burning the plant. For Backster, this could mean only one thing: the plant had somehow sensed his thoughts or intentions, and was responding. It's a leap of faith Backster would take several times in the coming decades. Over the years of his pseudo-scientific research, Backster attached polygraph leads to yogurt, bacteria, chicken eggs, human semen, and plants. Each substance or object seemed to respond—even at a great distance—to the thoughts of humans. Although Backster's work received little attention, or at least little positive attention from scientific publications, the idea of telepathic plants spread in popular forums like Harper’s Magazine.

Like Maude, Backster himself was caught in a sort of trend. Teresa Castro writes that, in the 1970s, many people saw plants as, "not only being able to communicate, but as communication systems in themselves." Through the cybernetics paradigm and systems theory, plants were "understood in terms of inputs and outputs" which could be stimulated, transmitted, and recorded. These metaphors have extended to humans, as well, though they may feel more like common sense than a particular philosophical outlook. For instance, smart watches record vital signs—signals from the body about its state. Biohacking schemes promise that you can message your body in a certain way to produce a certain kind of feedback. We’re blobby radio-controlled gizmos, in our minds.

Birgit Schneider traces this sort of thinking back to Norbert Wiener's 1948 book, Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. A "founding tome of cybernetics," Wiener's book describes technical sensor systems (radar, for example) as "sense organs" and, thereby, makes it possible to also ask: How are animal (or plant) senses like a radar system? In other words, how might a body send and receive simple signals through electronic means? According to Schenider, Wiener’s thought laid the groundwork for Backster's primary assumption: that plants sense, respond to, and interact with the world like a machine, which is to say, like a human. All this communication, all these interactions, were presumed to use electricity as a constitutive medium.

While Backster was caught in an intellectual trend, it's likely he spurred a new behavioral trend in the form of talking to, playing music for, or otherwise sharing sonic space with plants. According to a 1981 report by Armando Simón, Backster's work, "led to a 'talk to your plants' fad so that the plants would grow better as a result of the extra attention." It's an appealing hypothesis to draw from Backster's premise: plants work like machines and should respond positively or negatively (by growing or not growing) based on the signals we send to them. A friendly voice might be received as an invitation to grow, while an angry growl could cause botanical shrinkage. Backster's report was followed by books, magazines, and records which gave advice on how to acoustically induce plant growth.

In 1970, retired dentist George Milstein released a record titled Music to Grow Plants. Across each track, a high-pitched whine, designed to encourage phyto-lushness, rings out over inoffensive, if now kitschy, elevator music. That same year, CBS aired footage of an experiment in which plants were exposed to two types of music: American rock and Indian classical. The experiment appeared to demonstrate that rock music was deleterious to plants, but that Ravi Shankar's tunes, along with Western classical and jazz, had a beneficial impact. By 1971, American Home writer Lawrence V. Power was describing plants as "gregarious," and suggesting that they do best when grouped together. Perhaps the most popular outgrowth of this trend is Mort Garson's 1976 album, Mother Earth's Plantasia—a ten-track work performed on the Moog synthesizer.

While some gardeners held out hope that Bach or Bernard Shaw might get their rubber tree to rally, the sound-for-plants trend also faced its mockers. Simón's 1981 article groups talking to plants with similar media-based trends: seeing UFOs and collecting shark teeth after watching Jaws. In a 1984 book review for Yale Journal of Biological Medicine, Robert W. Arnold quips, "If talking to plants makes them grow, then showing them this book will surely make them blush because Pollen is an uninhibited and amply illustrated discussion of plant genitalia and plant airborne reproductive cells."

In 1971, though, Tuckahoe housewife Maude Findlay, who sauntered through her living room in a floral print apron while berating her begonias, was still on the cutting edge. Maude is in the midst of lecturing her plants when her daughter, Carol, flies through the front door. A doorside Schefflera is pushed by the gust of wind produced by the opening and closing of a door. Carol is a 20-something single mother who lives with Maude and Maude's husband, Walter. Carol informs Maude that there's a Black man outside their home and he's carrying a picket sign. It reads:

"A Slum Lord Lives Here"

At first, Maude doesn't believe Carol. She looks out the window to see for herself, to read those words. To understand Maude's reaction, it might be helpful to know a bit about the character. Maude is a liberal. That is to say, she votes reliably Democrat and holds fundraising parties for political candidates. She insists on women's rights, and insists on telling Black women how they ought to talk about themselves. I have no doubt she would have donned a pink pussy cap a few years back. So, a man accusing Maude of being a slum lord, and especially a Black man accusing her of being a slum lord, is an intense threat to her sense of self. A few moments after looking out the window, after confirming her nightmare, things get worse for Maude. The phone rings. It’s her best friend, Vivian. Viv says everyone at the grocery store is already talking about the man with the picket sign. Maude's liberal reputation is ruined.

And don't forget: the plants are listening, too.

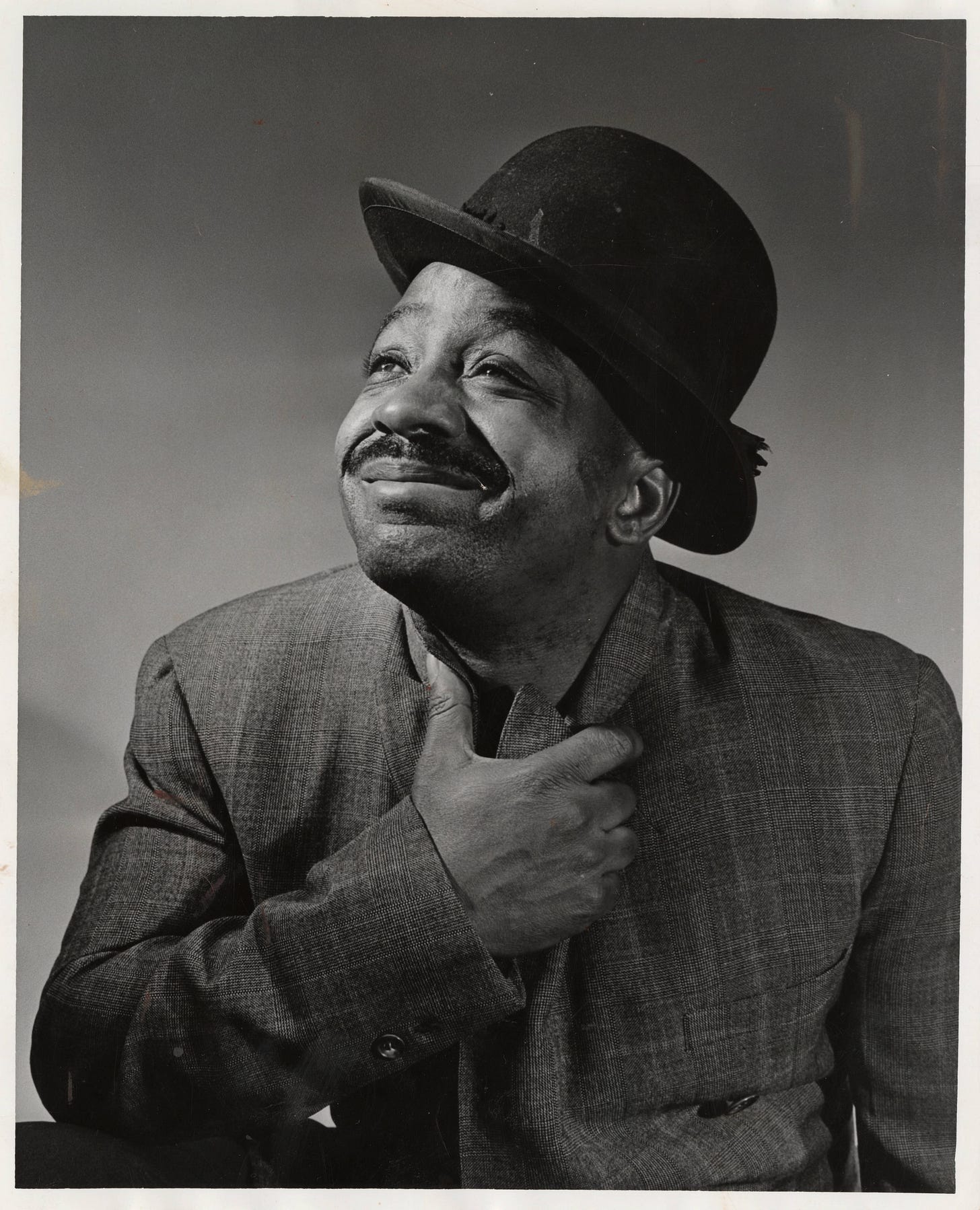

In the first few minutes of the episode, all is revealed: Walter, Maude's husband, is part of a real estate syndicate that owns a Harlem tenement. Maude's an investor, too. She signed the papers absentmindedly while watching television one night. Neither of them paid enough attention to know where the money was going exactly. The man outside, George Washington Carver Williams, lives in the tenement the Findlays partially own. In an attempt to explain their ignorance to Mr. Williams, and to apologize for their involvement, Maude and Walter invite Mr. Williams inside. Maude and Walter tell Mr. Williams that they put their money in a "tax shelter." He corrects them: they put it in a tenement. They go on to explain what a tax shelter is. He already knows what a tax shelter is: "You talking about stealing." After their chat, Mr. Williams heads back outside to resume his picketing. On the way out the door, he stops by Maude's houseplants.

"You got some lovely plants here. You know, if you talk real nice to them, they'll grow real special."

Mr. Williams says he can't keep houseplants at the tenement—the bugs will eat them. He talks to the cockroaches, though. "We're getting results that would stagger the imagination." One roach is as big as a Volkswagen.

Maude talks to her plants to get them to do what she thinks they ought to do: grow. But why does Mr. Williams talk to the bugs? We can safely assume he doesn’t want bigger bugs, so what other reasons might he have?

In "Manual for Talking to Plants," a short story by Morgan Day, the narrator volunteers at a local gardening help hotline. People talk to her about their plants, and about talking to those same plants.

"Under the guise of talking about plants, people liked to tell me about themselves. They told me about their depression, worried that the plants were absorbing their feelings. They told me gardening was their only escape and asked how they could improve so that eventually the plants would grow larger than them."

One man, Jim, calls in repeatedly. He's looking for proof that talking to plants stimulates their growth, and he wants to make music by hooking electronic leads up to their leaves. Jim lives in Phoenix; the narrator, in Tucson. He tells her about his life, and about his great difficulty in knowing what to say to plants. He's worried he'll bore them. In an effort to keep the plants on the line, Jim begins to fabricate a life just for the plants. He tells them he's a reporter working a beat in New York City, seeing every genre of ghastly urban event. The person his plants get to know, through his words at least, has an adventurous life—unlike his own. The plants grow larger, lusher, suggesting they are more interested in a good story than the truth. It’s what Jim feared. Still, talking to his plants gives Jim a way to be someone else, or maybe to explore who else he is.

Through Morgan Day’s story, we can imagine that Mr. Williams' bugs might be confidants. They share the same living conditions, are treated with similar levels of respect by the Maude Findlays of the world. Why not talk to them? Like Jim, Mr. Williams might be talking to the bugs about the lives he would like to live. He's already in New York City, but maybe he dreams of the Phoenix summer night shimmer. Maybe, in this way, plants aren't so special. We can talk to anything and get a response inside ourselves. We generate and receive the signal. Plants and bugs are just relays.

That's not to say plants are meaningless in Maude, or in general. Houseplants in the 1970s were a sign of taste. "The potted palm and the home-grown avocado tree have, in fact, become as popular on the contemporary scene as the Eames chair or the Parsons table," James V. Lawrence wrote in 1971. The Eames chair wasn't a bargain basement design object, of course, and Maude's houseplants are likewise a sign of disposable income. Talking to plants is a sign of disposable time. Mr. Williams has little of either. The rent he pays to the Findlays makes it possible for Maude to have and talk to houseplants. Her houseplants bring an infestation to Mr. William's home. They make it impossible for him to have a plant to talk to. Thinking about Maude's houseplants this way, we can to see another reason Mr. Williams talks about talking to bugs: to upset Maude. Maybe, and probably, he doesn't talk to bugs at all, but he knows that the idea of doing such a thing taints Maude's leisure activity with the economic realities that make the same activity possible. She's a bit hollow, a bit of a trend-tracker, and he's mocking her for it.

As the episode develops, Maude and Walter seek a way to offload their investment in the tenement. Eventually, they sell their share to a faceless third party, through their accountant who only appears via telephone call. Somewhere, someone else is moving money without thought, and their spider plants are listening in. The Findlays share the news with Mr. Williams who, for all the obvious reasons, really couldn't care less.

The next morning, Walter struts past Maude’s houseplants, who remain in the foreground of the living room. From his bathrobe, he tells them that Maude's love and care, which he received the night before, made him grow and grow. He assures them her love and care will do the same for them. Maude, flattered, overhears him from a few paces back. Then, she chides him: He shouldn't talk that way in front of the begonia. It's only a baby. Everything is as it had been the morning prior. In this Tuckahoe home is a normal, liberal family. Mr. Williams, somewhere, protests another houseplant enthusiast, but Maude is off the hook.

At the start of the next episode, most of the houseplants have disappeared from the Maude set, with the exception of the doorside Schleffera. Maybe—and I know I'm sidestepping production realities here—Maude couldn't bear to have these plants listening anymore. And maybe that's not such a funny thing to suggest. Towards the middle of the "Slum Lord" episode, Maude's housekeeper storms through the front door. Minutes before, Florida, played by Esther Rolle, had quit in solidarity with Mr. Williams. Now, she's come back to rescue a botanical ally—an African violet in Maude's collection. As Florida enters the room, the spider plant opposite the Schleffera swings. Its movement tells me it's a growing plant, not a plastic dupe. Production seems to have brought real, living plants onto the set. They sweltered in the set lights, like the actors. They heard lines delivered with expertise, and lines fumbled in amateur fashion. Whether or not the plants cared about any of the sonic vibrations that reached them—and I'm just absolutely sure that they did not—they served as the suggestion of a listener, a receiver. They were a live studio audience, present for the revelation that Maude Findlay is a slum lord. Plants are a kind of conscience, not because they care about the ethics of what we do, but because we want to believe that, if they did care, they would approve of our actions. And we want to believe that we could measure, could perceive that approval, too.

But Maude Findlay’s plants won't grow, which she understands as the most drastic kind of sympathetic action against her. Her story’s just not as good as Jim’s fictional NYC capers, and her nonfiction actions are repugnant. You open the door to her house, and there’s a photosynthetic picket sign. It sends out a signal:

“Maude Findlay is a slum gardener.”

In reality, plants transport water upward using siphon-like activity, not mechanical action. Water evaporates from the leaves, drawing more water upward through the xylem.

Really really good. This is the first time I’ve thought of the concept of a parasocial audience — plants are who we think are listening to us, the same way we think we can weigh in on the lives of Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce.

…am I writing for plants when I post on substack?